Causes of hypertension in cats

The reasons that contribute to the development of hypertension in cats are different, here are the main ones:

- CRF (chronic renal failure). To compensate for the function of damaged kidney nephrons, blood pressure increases to increase the volume of blood for filtration.

- Hyperthyroidism is a functional disorder of the thyroid gland, in which the synthesis of hormones increases. This leads to faster metabolism. As a result, the heartbeat intensifies and increases, and as a result, the heart increases in size, which leads to an increase in blood pressure.

- Heart failure

- Diabetes

- other reasons

Causes of increased blood pressure

Causes of hypertension in cats:

- idiopathic hypertension

(the cause of the disease has not been identified); - Chronic renal failure in cats

- as feline renal failure progresses, fewer and fewer intact nephrons remain that can adequately filter the blood. Compensatory kidneys try to pass through themselves an increasing volume of blood per unit of time. This becomes possible with a significant increase in blood pressure. It is estimated that 60% of cats with ESRD have hypertension; - feline hyperthyroidism

– the feline thyroid gland is located in the neck and plays an important role in regulating internal metabolism. When benign growth of the gland occurs, excess production of the hormone thyroxine is observed, which leads to an increase in metabolic rate and an increase in heart rate. Consequently, blood pressure also increases; - heart failure

; - diabetes

; - hyperaldosteronism

.

Symptoms of hypertension in cats

The organs that are at risk when hypertension occurs in cats are:

Eyes

. With increased blood pressure, hemorrhages into the vitreous body and the anterior chamber of the eye are possible. Often one eye is more affected than the other. In addition, minor hemorrhages, swelling and detachment are noted in the retina. Degenerative lesions are common. Vision is impaired, up to the development of blindness, often irreversible.

Nervous system and brain

. Hypertension in cats causes disturbances in the vestibular apparatus, this is manifested by strange behavior of the animal, changes in gait (shaky and sluggish), convulsions, paresis, and paralysis. Since the nervous system is saturated with small blood vessels, in cats with hypertension this system is often affected, including the brain.

The cardiovascular system

. Hypertension in cats causes heart murmurs and increased heart rate. Less commonly, there may be manifestations of arrhythmia and shortness of breath. All of this is exacerbated by cardiovascular disease, since it is unlikely that hypertension is the underlying cause of heart failure. On X-ray examination, hypertension in cats may manifest itself as an enlarged heart, particularly the left ventricle.

Kidneys

. Hypertension in cats causes problems with normal kidney function.

General clinical picture

with hypertension in cats, it is very vague; at the initial stage, it is impossible to observe specific signs of this disease. Then there comes a time when hemorrhages appear in the eyes, reaching the point of retinal detachment, and worried owners turn to a veterinarian about their pet’s blindness.

Accordingly, it is necessary to observe more closely the behavior of your pets. When the above primary signs appear, it is important to remember about possible hypertension in cats. In addition, cat owners should be wary of their depressed, lethargic and withdrawn behavior.

Systemic arterial hypertension in cats

Systemic hypertension (an abnormal increase in systemic blood pressure) as a circulatory pathology is often reported in older cats. A high incidence of systemic hypertension is observed in cats with chronic renal failure (61%) and hyperthyroidism (87%) (Kobayashi et al, 1990). But at the same time, hypertension also occurs in cats in the absence of renal failure and euthyroidism (normal thyroid status). Because untreated hypertension in cats can lead to serious neurological, ophthalmological, cardiac and nephrological disorders, treatment of these patients is strongly recommended. In addition, specific antihypertensive drugs can significantly influence end-organ function and long-term prognosis.

Systemic hypertension usually presents as a complication of another systemic pathology and is therefore classified as secondary hypertension. However, in some cases where the cause of HS is not established, in the process of a full examination they speak of primary or idiopathic hypertension.

Epidemiology

As mentioned above, hypertension is more common in older cats, with an average age of 15 years and a range of 5 to 20 years (Littman, 1994; Steele et al, 2002). It is not clear whether an increase in blood pressure in healthy older cats is normal or whether this should be regarded as an early subclinical stage of the development of a pathological process. No breed or gender predisposition to hypertension has been identified in cats.

Pathophysiology

Although systemic hypertension is frequently identified in cats with chronic renal dysfunction, the relationship between elevated blood pressure and renal damage as an underlying cause is not clear. Vascular and parenchymal renal diseases in humans are proven causes of hyperrenergic hypertension. Moreover, an increase in the volume of extracellular fluid is one of the mechanisms for the development of hypertension in patients in the late stages of kidney disease (Pastan & Mitch, 1998). There is evidence that cats with naturally occurring hypertension and renal failure do not have increased plasma renin levels or activity or increased plasma volume (Hogan et al, 1999; Henik et al, 1996). This suggests that some cats have primary (essential) hypertension and that the kidney damage is secondary and a consequence of chronic glomerular hypertension and hyperfiltration.

Likewise, the relationship between hyperthyroidism and hypertension in cats is not well defined, even though the incidence of hypertension is high in cats with thyrotoxicosis. Hyperthyroidism leads to an increase in the number and sensitivity of myocardial β-adrenergic receptors and, as a consequence, increased sensitivity to catecholamines. In addition, L-thyroxine has a direct positive inotropic effect. Consequently, hyperthyroidism leads to increased heart rate, increased stroke volume and cardiac output, and increased arterial blood pressure. However, in cats, no significant relationship has been found between serum thyroxine concentrations and changes in blood pressure (Bodey & Sansom, 1998). In addition, in some cats, with proper and effective treatment of hyperthyroid status, arterial hypertension may persist. Thus, it is assumed that in a proportion of cats with hyperthyroidism, hypertension is independent of hyperthyroid status. Other unlikely causes of hypertension in cats include hyperadrenocorticism, primary aldosteronism, pheochromocytoma, and anemia.

Hypertension in the absence of renal or thyroid disease in cats suggests that in some cases, as in humans, systemic hypertension can be considered a primary idiopathic process involving increased peripheral vascular resistance and endothelial dysfunction.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs are usually derived from damage to the target organ (brain, heart, kidneys, eyes). As blood pressure rises, autoregulatory vasoconstriction of arterioles occurs to protect the capillary beds of these highly vascularized organs from high pressure. Severe and prolonged vasoconstriction can ultimately lead to ischemia, infarction, and loss of capillary endothelial integrity with edema or hemorrhage. Cats with hypertension may exhibit symptoms such as blindness, polyuria/polydipsia, neurological signs including seizures, ataxia, nystagmus, hind limb paresis or paralysis, dyspnea, and epistaxis (Littman, 1994). Rarer possible signs include “fixed gaze” and vocalization (Stewart, 1998). Many cats do not show clinical signs, and hypertension is diagnosed after murmurs, galloping rhythms, electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities are identified. In cats, systemic hypertension is often associated with left ventricular hypertrophy. Usually this is moderate hypertrophy and asymmetric septal hypertrophy of the left ventricle. Dilatation of the ascending aorta is detected radiographically or echocardiographically, but it is not clear whether this finding is due to hypertension or normal age-related changes. Cats with systemic hypertension often have left ventricular diastolic dysfunction due to decreased left ventricular wall relaxation.

Wide variability in electrocardiographic changes includes ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, atrial or ventricular complex dilatation, and conduction disturbances. Tachyarrhythmias are resolved with proper hypertension treatment.

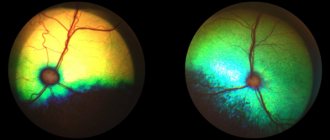

Acute blindness is a common clinical manifestation of systemic hypertension in cats. Blindness usually occurs due to bilateral retinal detachment and/or hemorrhage. In one study, 80% of hypertensive cats had hypertensive retinopathy with retinal, vitreous, or anterior chamber hemorrhages; retinal detachment and atrophy; retinal edema, perivasculitis; retinal artery tortuosity and/or glaucoma (Stiles et al, 1994). Retinal lesions usually regress with antihypertensive therapy, and vision returns.

The central nervous system is prone to damage due to hypertension because it is replete with small vessels. In cats, these injuries can cause convulsions, head tilt, depression, paresis and paralysis, and vocalization.

Chronic hypertension may cause kidney damage as a result of changes in afferent arterioles. Focal and diffuse glomerular proliferation and glomerular sclerosis may also develop (Kashgarian, 1990). Following impairment of renal function, chronic systemic hypertension causes a sustained increase in glomerular filtration pressure, which plays a key role in the progression of deterioration of renal function (Anderson & Brenner, 1987; Bidani et al, 1987). Proteinuria and hyposthenuria are uncommon in cats with hypertension, but microalbuminuria is observed (Mathur et al, 2002).

Ophthalmological examination

The most common reason for a cat owner to present with arterial hypertension is acute blindness. The owner notes that the cat has become less active in moving around the room, has stopped jumping on furniture, or is missing its jump. In some cases, the owner does not suspect that the cat’s vision is sharply reduced or absent, since the cat, even completely blind, continues to navigate a familiar room using other senses. This is one of the reasons why the cat owner comes to the clinic late.

The main complaints of owners are a dilated “frozen” pupil, blood inside the eye, a change in the fundus reflex, and loss of vision.

To identify retinal pathology it is necessary:

- check pupillary motor reactions;

- check reaction to bright light (dazzle reflex);

- check the reaction to a threatening gesture;

- conduct a cotton ball test to determine whether a cat can track the movement of objects in its field of vision;

- measure intraocular pressure;

- examine the anterior segment of the eyeball using a slit lamp;

- perform an ophthalmoscopy;

- If necessary, perform an ultrasound of the eyeball.

A set of these manipulations will help determine the extent of retinal damage and, to some extent, give a prognosis for the restoration of vision.

The researcher receives the most valuable information about the condition of the retina thanks to ophthalmoscopy.

The fundus picture of a cat has great variability. It is important to distinguish between normal and pathological. It must be remembered that the absence of tapetum or pigment can occur in a completely healthy animal.

Signs of pathology are:

- abnormal condition of the vessels (their diameter, direction of travel) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 7)

Fig. 1. Fig. 2. - changes in the area of the optic nerve head (Fig. 7)

- the presence of hemorrhages of various sizes (Fig. 1, Fig. 3)

Fig. 7. Fig. 3. - limited or extensive areas of retinal detachment (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5)

Fig. 4. Fig. 5. - presence of blood in the vitreous body (Fig. 6)

Rice. 6. Fig. 8.

In cases where ophthalmoscopy is impossible (with extensive hemorrhage into the vitreous body, with cataracts), it is necessary to perform an ultrasound of the eyeball. The presence of a hyperechoic membrane that connects to the fundus in the area of the optic nerve head indicates retinal detachment (Fig. 8).

Suspicion of arterial hypertension in a cat can be based on the presence of characteristic retinal lesions. However, it is necessary to exclude other causes of retinal detachment and/or hemorrhages. Arterial hypertension must certainly be confirmed by measuring blood pressure. Blood pressure measurements should be performed to confirm or refute the presence of hypertension in cats with left ventricular hypertrophy, renal dysfunction or hyperthyroidism, and in cats over 7 years of age with murmurs or a galloping rhythm. Blood pressure measurements should also be taken in cats with the above-described signs of brain damage.

Hypertension in cats was defined as an indirect systolic pressure greater than 160 mmHg. Art. (Littman, 1994; Stiles et al., 1994) or 170 mmHg. Art. (Morgan, 1986) and diastolic blood pressure more than 100 mmHg. Art. (Littman, 1994; Stiles et al., 1994). However, blood pressure will increase with age in cats and can exceed 180 mmHg. Art. systolic and 120 mm Hg. Art. diastolic pressure in apparently healthy cats over 14 years of age (Bodey and Sansom, 1998). Thus, a diagnosis of hypertension can be made in a cat of any age whose systolic blood pressure is 190 mmHg. Art. and diastolic pressure 120 mm Hg. Art. Cats with a clinical picture consistent with hypertension and a systolic pressure between 160 and 190 mm Hg. Art. should also be considered to have hypertension, especially if they are under 14 years of age. In the absence of clinical signs of hypertension, systolic blood pressure is from 160 to 190 mm Hg. Art. and diastolic pressure between 100 and 120 mmHg. Art. repeated measurements are necessary several times throughout the day or possibly several days.

Early diagnosis and treatment of cats with systemic arterial hypertension is important. Although not all cats exhibit clinical signs, failure to promptly diagnose and treat them can lead to extremely undesirable consequences.

The main goal of treatment is to prevent further damage to the eyes, kidneys, heart and brain. This is achieved not only by lowering blood pressure, but also by improving blood circulation in target organs.

Numerous pharmacological agents are available for use as antihypertensive agents, including diuretics, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel antagonists, direct-acting arterial vasodilators, centrally acting α2-agonists, and α1-blockers. .

Cats with hypertension tend to become refractory to the antihypertensive effects of adrenergic blockers such as prazosin, as well as direct-acting arterial vasodilators such as hydralazine. In addition, long-term use of direct-acting drugs often leads to undesirable stimulation of compensatory neurohumoral mechanisms. Diuretics, β-blockers, or a combination of both are effective in lowering blood pressure in most hypertensive cats but do not reduce end-organ damage (Houston, 1992).

According to Poiseuille's law, blood pressure is determined by the product of systemic vascular resistance and cardiac output, so the decrease in blood pressure resulting from the use of diuretics and beta-blockers results from a decrease in cardiac output. These drugs lower blood pressure through a mechanism that reduces flow to target organs, thereby compromising myocardial, renal, and brain perfusion. At the same time, calcium channel antagonists, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers reduce blood pressure by reducing vascular resistance. This mechanism is more effective in improving target organ perfusion. Calcium channel antagonists, in particular, lack myocardiodepressive effects, and ACE inhibitors have, in fact, shown beneficial effects on renal function, coronary perfusion and cerebral perfusion in people with hypertension (Houston, 1992; Anderson et al, 1986). Centrally acting α-adrenergic agonists also lower blood pressure by reducing vascular resistance and are indicated to maintain target organ function. Diuretics and beta-blockers reduce cardiac output, stroke volume, coronary and renal blood flow, increasing vascular resistance of the renal vessels. In addition, these drugs do not reduce left ventricular hypertrophy. On the other hand, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and centrally acting drugs have the opposite effect.

Amlodipine is a long-acting antihypertensive drug belonging to the calcium channel blockers. This drug relaxes the smooth muscles of blood vessels, blocking the influx of calcium. Its main vasodilating effect is a systemic decrease in vascular resistance. In addition, this effect extends to the coronary arteries. This drug is safe and effective even in cats with renal dysfunction when administered orally at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg once daily. When taken daily, amlodipine reduces blood pressure within 24 hours (Snyder, 1998). In addition, cats do not become refractory to amlodipine, and with long-term therapy, a persistent therapeutic effect occurs.

ACE inhibitors such as enalapril, ramipril and benazepril are also good choices for the treatment of hypertension in cats. In the Russian Federation, the drug Vazotop®R (MSD Animal Health) has become widespread. The active ingredient of the drug is ramipril. Ramipril has unique properties that distinguish it from other ACE inhibitors used in veterinary medicine.

However, these drugs are often ineffective as monotherapy in cats. ACE inhibitors may be best used in combination with amlodipine.

In cats resistant to amlodipine or ACE inhibitors, only a combination of these drugs can safely provide adequate blood pressure control. When adding ACE inhibitors (enalapril or benazepril) to amlodipine therapy, doses of 1.25 to 2.5 mg/cat/day are used). Also, some cats receiving this combination of drugs show improvement in kidney function. Experimental evidence shows that the combination of these two classes of antihypertensive drugs not only effectively lowers blood pressure, but also maximizes target organ protection (Raij & Hayakawa, 1999). The angiotensin receptor blocker irbesartan in combination with amlodipine has been shown to be effective in some cats refractory to ACE inhibitors.

Cats with neurological disorders due to brain damage require aggressive treatment to quickly lower blood pressure. Amlodipine and ACE inhibitors have a relatively slow hypotensive effect and require 2-3 days to reach the peak of the hypotensive effect. In such clinical situations, intravenous administration of nitroprusside would be more effective for rapid relief of a hypertensive crisis. However, safe use of this drug requires careful dose titration using an infusion pump (1.5-5 mg/kg/min) and continuous blood pressure monitoring. Hydralazine may be used as an alternative to nitroprusside when rapid blood pressure reduction is not required. This drug is usually given orally every twelve hours, starting at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg and increased as needed to 2.0 mg/kg every 12 hours. Caution is advised when using fast-acting, potent antihypertensive drugs to treat hypertensive crises. A rapid and severe drop in blood pressure can lead to acute cerebral ischemia and thereby worsen neurological deficits.

Target organs for hypertension

| Organ/System | Effect | More often the effect occurs when | A comment |

| Kidneys |

| > 160 mmHg Art. | It is often difficult to differentiate kidney disease as a cause or effect of systemic hypertension |

| Eyes |

| > 180 mmHg Art. | Hypertensive retinopathy/ Choriopathy |

| Brain |

| > 180 mmHg Art. acute | Clinical signs of ischemic and hemorrhagic brain damage. |

| Heart |

| In cats, myocardial changes may resolve with successful antihypertensive therapy |

Diagnosis of hypertension in cats

Diagnosis of hypertension in cats, like other diseases, is carried out comprehensively. Regular blood pressure measurement is important. For this purpose, equipment is used very similar to that used for people. The cuff is placed on the cat's paw or tail. The fact that hypertension affects the eyes of cats is also taken into account when diagnosing. The veterinarian pays attention to the blood vessels of the fundus and retina, and even in the initial stages of this disease, a specialist can detect pathological changes in them. In advanced and severe cases of hypertension in cats, retinal detachment and hemorrhages in the eye can often be found. Rarely, pathology is observed in one eye; more often, two eyes are affected at once.

The city veterinary oncology clinic has a highly qualified specialist – an ophthalmologist. His professionalism is confirmed by many letters, certificates and treated patients. And high-precision and modern equipment for eye examination allows you to quickly and accurately make the correct diagnosis and begin treatment immediately.

When measuring blood pressure, it is important to take into account the fact that cats may be nervous and frightened by the manipulation. Accordingly, blood pressure readings will be incorrect. In this regard, the diagnosis will be erroneous, and subsequent treatment may also not give the desired result. Therefore, it is helpful to give your cat time to adapt to the environment where the blood pressure will be measured.

Hypertension in cats.

Based on materials from the website www.icatcare.org

Hypertension

(hypertension) is the medical term used for high blood pressure. This disease is quite common in older cats.

Feline hypertension usually develops as a result of other medical problems (called 'secondary hypertension'), although primary hypertension (hypertension without other "underlying" medical conditions) can also occur in cats. Unlike humans, who are more likely to have primary hypertension (also known as 'essential hypertension'), cats are more likely to have secondary hypertension. In most cases, secondary hypertension in cats is caused by chronic kidney disease, but other diseases can also lead to its development. A connection has also been established between hypertension and hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid gland) in cats.

Hypertension is dangerous for the cat’s entire body. The following organs are most vulnerable:

Eyes.

There may be bleeding in the eye and abnormalities in the retina, such as swelling and detachment. As a result of these disorders, the cat's vision can be affected and even blindness, often irreversible, can develop. In some cases, hemorrhages in the anterior chamber of the eye may be visible without the use of special equipment.

Brain and nervous system.

Neurological signs may cause bleeding in these areas of the cat's body. such as strange behavior, staggering or drunken gait, seizures, dementia and coma.

Heart.

Gradually, the muscles in one of the main chambers of the heart (the left ventricle) thicken as the heart finds it more difficult to perform its pumping tasks when pumping high-pressure blood. In very severe cases, this can lead to the development of chronic heart failure. The cat may experience shortness of breath and lethargy.

Kidneys.

Over time, high blood pressure increases your risk of developing kidney problems. In cats with kidney problems, hypertension can significantly complicate the disease over time.

Diagnosis of hypertension in cats.

Because hypertension is often the result of other diseases, cats may exhibit symptoms of an underlying disease. For example, in hyperthyroidism in cats with high blood pressure, the main clinical signs may be weight loss (despite an excellent appetite) and hyperactivity.

Many cats may not show any specific signs of hypertension until the disease reaches a stage where the eyes begin to bleed or the retina detaches - these cats are often brought to the vet for sudden blindness. Therefore, early detection of hypertension is very important to alleviate the disease and reduce the danger to the eyes and other organs of the cat's body.

Some cats suffering from hypertension appear depressed, lethargic, and withdrawn, even if there are no signs of damage to other organs. Many owners note the restoration of their cat's normal behavior after starting treatment for hypertension. It appears that with severe hypertension, cats, like humans, may suffer from headaches.

To detect hypertension early, it is recommended to regularly measure blood pressure in cats over 7 years of age, as hypertension is more common in older cats. Initially, this can be done once a year, but as the cat gets older, the pressure should be monitored at least twice a year, in addition, pressure monitoring should be carried out at any visit to the veterinarian.

Constant monitoring of blood pressure should be carried out in cats suffering from kidney disease, hyperthyroidism, heart disease, sudden blindness, as well as in cats with other visual impairments and neurological disorders, in order to prevent the development of hypertension in time.

Many clinics have the appropriate equipment to measure blood pressure in cats. Often these devices are similar to those used by humans, with an inflatable cuff placed over the cat's paw or tail. The process of measuring pressure takes a couple of minutes, does not cause pain and is easily tolerated by most cats.

A detailed eye examination is also important to diagnose hypertension in cats. In the initial stage of the disease, small changes in the blood vessels of the fundus and retina can be detected. In more severe cases, changes can be significant, including retinal detachment and bleeding in the eye. Typically, abnormalities are observed in both eyes of a cat, but (less commonly) may be found in only one.

In the absence of devices for measuring blood pressure, it is possible to diagnose hypertension during an eye examination, especially taking into account the dynamics of changes after the start of treatment. However, with the help of special devices for measuring blood pressure in cats, diagnosis and monitoring of the results of therapy is much more effective.

Treatment of hypertension in cats.

After confirmation of hypertension, treatment of cats is carried out in two directions:

The first is treatment aimed at lowering blood pressure using antihypertensive drugs. Many medications are now available, usually based on amlodipine and benazepril.

The second is identifying and treating the underlying disease, such as kidney disease that causes hypertension. In some cases (for example, with hyperthyroidism), treatment of the underlying disease can also solve the problem of high blood pressure. Urine and blood tests are usually performed to identify the underlying disease.

It is also important to assess what complications of hypertension are present in the cat (for example, eye diseases) in order to properly control them during therapy. Cats have a very wide variability in response to antihypertensive drugs, and blood pressure stabilization may take varying periods of time. It may be necessary to change medications, change the dose and/or frequency of administration, or use more than one drug.

Response to therapy is best monitored by regular blood pressure measurements and eye examinations. In cats with kidney disease, it is important to continually monitor kidney function during treatment.

Prognosis for the treatment of hypertension in cats.

Cats with primary hypertension (without an underlying medical condition causing the high blood pressure) can usually control the disease and prevent complications, such as those that threaten vision.

In the case of secondary hypertension, the long-term prognosis directly depends on the nature and severity of the disease causing the increase in pressure. In all cases, it is important to monitor your blood pressure carefully and regularly to avoid complications.

Treatment of hypertension in cats

Treatment, like diagnosis, is complex. Due to the fact that hypertension is only a consequence of the underlying disease, after primary treatment aimed at reducing blood pressure with the help of modern medications, it is necessary to proceed to the second direction. Veterinarians of the city veterinary oncology, attending international veterinary conferences and congresses, monitor the latest trends in the treatment of diseases and the emergence of new drugs.

The second direction of treatment is to eliminate the underlying disease. In some cases, when it is eliminated, the pressure normalizes, and the problem of hypertension in cats goes away. It is necessary to carefully monitor those organs that were affected by increased pressure.

Hypertension in cats - caring for your pet

The level of care required for a cat with hypertension depends on the cause. Ongoing damage to target organs is also important. The degree of progression of the disease and the risk for further development of lesions. Most cats have secondary hypertension. So the underlying disease needs to be diagnosed and controlled first.

In some cases, when the underlying disease is controlled, secondary arterial hypertension resolves. However, some cats will still remain hypertensive due to damage to small vessels. These damages persist after the underlying disease has resolved. Despite treatment of the underlying disease, if hypertension persists or in the presence of target organ damage, antihypertensive therapy is necessary.

Most cats with hypertension do not require emergency treatment, and the patient's blood pressure can be lowered gradually. However, in cases of hypertensive choroidopathy/retinopathy or encephalopathy, more urgent and drastic measures may be required to lower blood pressure.

When visiting a cat clinic for diagnosis or treatment of hypertension, it is important to provide the doctor with the names and dosages of medications used. We also need all the results of tests that have already been carried out. Including data on blood pressure measurements and by what device, type of cuff and in what position of the animal's body these data were obtained.

Prognosis for hypertension in cats

As the truism goes, prevention is the best cure. If you follow this rule, your pet needs regular visits to the veterinarian. This is best done in those clinics that have modern equipment that meets the latest global trends and, of course, professional veterinary specialists. All this is available at the city veterinary oncology center “Pride”.

It is recommended for cats over 7 years of age to periodically measure blood pressure. This will allow you to notice the onset of the disease in time and give you a chance to stop the pathological process due to timely treatment. During this manipulation, cats do not experience any unpleasant sensations and calmly tolerate this procedure.

The prognosis for hypertension directly depends on the responsibility of the owner to his pet, who can notice the initial stage of the disease in time, or conduct regular preventive visits to the veterinarian. Thanks to this, you can avoid the occurrence of the disease, or count on a positive prognosis when hypertension occurs in cats.

Author of the article: veterinary therapist Elena Sergeevna Avdasheva

Basic information

Hypertension is the medical term used to refer to high blood pressure. Several years ago, everyone confidently believed that this problem was characteristic exclusively of humans, but now information has appeared that fully confirms the existence of this pathology among our smaller brothers. Cats also suffer from high blood pressure.

This disease is divided into two types: primary and secondary. In cats, it is secondary pathology that is common, that is, a pathology that develops under the influence of some other diseases. Primary arterial hypertension in animals is extremely rare, but its possibility cannot be ruled out. Scientists and veterinarians suggest that in this case we can talk about a genetically determined defect.

Very often, problems with blood pressure occur when an animal has diseased kidneys. Chronic renal failure is most often to blame. If a cat has hyperthyroidism, he will certainly suffer from high blood pressure.

High blood pressure in cats: symptoms and treatment

The fact is that cats have a predisposition to chronic high blood pressure, especially cats whose age has already crossed the border of youth. Most often these are cats over 14 years old, but, alas, it occurs in younger ones. It is very important to identify high blood pressure in a cat as quickly as possible. In this case, the prescription of special drugs will have the best effect and will not allow many complications to develop, including the development of renal and/or heart failure. Cats even have a “special” disease, like humans – systemic arterial hypertension, which has extremely serious consequences.

The difficulty lies in the fact that when owners notice a deterioration in the cat’s well-being, based on such signs as:

- weight loss

- blindness

- development of increased thirst and increased fluid intake

- movement disorders, etc.,

the process has already gone far, so we recommend that cats over 6 years of age undergo tonometry at least once a year.

At the moment, the process of measuring blood pressure in cats is easy and painless (unlike, say, 10 years ago). In our VETMASTER center there is a special device that can be used to measure an animal’s blood pressure - PatMap.

This is a small, virtually silent device that allows you to accurately measure a cat’s blood pressure without exposing it to unnecessary stress, which, unfortunately, cannot be done with human tonometers.

The accuracy of the measurement is an extremely important factor, because the increase in blood pressure in a cat exceeds 190 mmHg. in systole and above 120 mmHg. in diastole clearly indicates pathology. The cat’s systole pressure between 160-190 indicates that you and I need to strengthen control over the cat’s condition, and perhaps conduct additional examinations. Check the function of the kidneys and thyroid gland, rule out diabetes mellitus, which is also not uncommon in older patients, conduct an echocardiography, that is, an ultrasound of the heart, to make sure that everything is in order.

If your kitty is prone to stress, when visiting veterinary clinics, before tonometry, you and her will be taken to a separate quiet room, where you will spend some time together so that the cat calms down, gets used to the smells and understands that she is not in danger. After this, it will be possible to measure the animal’s blood pressure.